In 2011, it had been over 90 years since anyone could buy a pint directly from a Minnesota brewery due to Minnesota’s new taproom law this was about to change. When discussing Minnesota’s taproom law, most people assume the law just overturned outdated blue laws remnant from the Prohibition Era. However, the legislation dealing with the taproom law was not technically a blue law since it was not designed to restrict access to alcohol on certain days but to reduce corruption in alcohol distribution. These laws instituted various versions, depending on the state, of what would be called the three tier system. The three tier system had two distinct purposes; one was to eliminate organized crime from the alcohol industry and the other was to end the pre-prohibition system of tied houses.

One may ask, what is a tied house and where did the idea come from? The tied house system originated in Great Britain’s brewing industry as a form of vertical integration where the pub was owned by the brewery. This system was abolished recently (in the 1990s) in the UK as to foster competition. The problem for British beer lovers (like the Campaign for Real Ale (CAMRA)) was that the pubs did not become independently owned but entered a different tied house system. Instead of the brewery controlling the pub, the pubs were purchased and controlled by giant “pubcos” (think Applebees.) CAMRA claims that the abolishment of the old tied house system not only led to the closure of local pubs but lowered the quality of the available ales.

What does this have to do with beer on the American side of the Atlantic? The United States had its own short lived experience with the tied house system. From the 1840s through the end of the nineteenth century the United States experienced its first beer renaissance with a large influx in immigration of German, Czech, and Scandinavian people. They brought with them beer culture and a lighter style of beer called lager. Many of these recent immigrants enjoyed a culture of social beer drinking. German immigrants in particular enjoyed socializing in large beer halls or gardens with their entire families. The most common day for this activity was Sunday when most working class people enjoyed a day off. Many initial Blue laws were designed to restrict the influence of immigrant culture by outlawing alcohol sales on Sundays. Many recent immigrants saw this not only as an attack on their culture but as a design to curb their political will by preventing them from publicly gathering. This coincided with the birth of the “dry” or Temperance Movement.

The temperance movement would first attempt to enact total prohibition at the state level with acts like the Maine Law of 1851. These ideas did not find much traction in the large German immigrant populations of Milwaukee and Chicago and would eventually fail. In Chicago, these forces would come to physical blows in the “Lager Beer Riots” when the Illinois Sunday Closure Law was enforced by Chicago’s new mayor Levi Boone in 1955. Ultimately, 31 saloon owners refused to be closed on Sunday and were promptly arrested. The civil unrest would eventually lead to these laws being reversed. Their failures fresh in their minds, temperance advocates devised a new strategy.

Their new strategy was to raise the licensing fee to levels that saloon owners could not afford. The new fees ranged from as low as $50 to over $500 in some areas. In order to save the retail establishments marketing their products, the breweries would step in with low interest loans or even direct ownership. The temperance movement viewed this adjustment as an acceptable change.

Beer, primarily due to its lower alcohol content, had long been viewed as a temperance beverage. With direct brewery involvement, it was assumed that beer would be exclusively served and the large companies would not tolerate vice, as in gambling or prostitution, in their establishments. Early on this was the case. For example, the Schlitz Palm Garden, built in 1896, was a 4,500 square foot Victorian inspired beer garden that served food, held orchestra concerts, displayed works of art, and feature a park for family picnics.

Beer, primarily due to its lower alcohol content, had long been viewed as a temperance beverage. With direct brewery involvement, it was assumed that beer would be exclusively served and the large companies would not tolerate vice, as in gambling or prostitution, in their establishments. Early on this was the case. For example, the Schlitz Palm Garden, built in 1896, was a 4,500 square foot Victorian inspired beer garden that served food, held orchestra concerts, displayed works of art, and feature a park for family picnics.

The growth of the brewing industry in the late 1800s created an increasingly competitive environment leading to an era known as the “Beer Wars.” During the Beer Wars the large breweries (e.g.Schlitz, Pabst, Busch, and so on) would cut their prices in half to drive out any competition. During this highly competitive time, many saloon keepers were also faced with increased pressure to obtain greater profits and more revenue. Faced with the increasing pressure, some unscrupulous saloon keepers turned a blind eye to gambling, prostitution, and other forms of vice in return for kickbacks.

Interestingly prior to the 1900s the Minneapolis city attorney D. F. Simpson and the wealthy Pillsbury family launched the Minneapolis Plan of 1884. The goal of the plan was to curb the political influence of saloons by confining them to business districts, thus eliminating the neighborhood saloon. When compared to other major American cities in the height of the era, the Twin Cities had one of the highest concentrations of tied houses. In 1908 only 38 of 432 saloons in Minneapolis were independently owned. For example, the Minneapolis Brewing Company had 131 saloons.

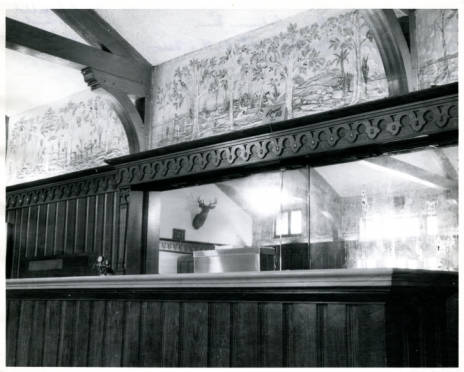

There were benefits to this system. First, many breweries spent lavishly on the construction of their tied houses. For instance, today Ward 6 in St. Paul is an example of a restored Hamm’s tied house. There are also many great examples of the most prolific tied house brewer, Schlitz, in Chicago. Slowly but surely the social problems associated with saloons were laid at the feet of the breweries giving the temperance movement firm footing to attack them. A marketing strategy giving free lunch to saloon patrons was often a focus for criticism as it seemed to promote daytime drinking. The marketing strategy put many industries in the pocket of the temperance movement because they saw daytime drinking as an attack on the productivity of their workers.

There were benefits to this system. First, many breweries spent lavishly on the construction of their tied houses. For instance, today Ward 6 in St. Paul is an example of a restored Hamm’s tied house. There are also many great examples of the most prolific tied house brewer, Schlitz, in Chicago. Slowly but surely the social problems associated with saloons were laid at the feet of the breweries giving the temperance movement firm footing to attack them. A marketing strategy giving free lunch to saloon patrons was often a focus for criticism as it seemed to promote daytime drinking. The marketing strategy put many industries in the pocket of the temperance movement because they saw daytime drinking as an attack on the productivity of their workers.

The tied house system was effectively ended in the United States with the passage of the Volstead Act in 1919. The laws repealing national prohibition resulted in the creation of state by state legislation and enforcement of a three tiered system of breweries, wholesalers, and retailers. The three tiered system prevents breweries from having a direct connection with the retail sales of their products. The idea was to prevent what was viewed as the monopolization of the brewing industry and increase tax revenue from breweries. One of the main drawbacks to this system was that it raised barriers for small producers to enter the market. The Taproom Law of 2011 only created a loophole in this system by allowing producers to sell their products on location.

Hopefully, with some background on the tied house system, we can now really appreciate how great it is to once again raise a pint at the brewery where the beer was born. Cheers!

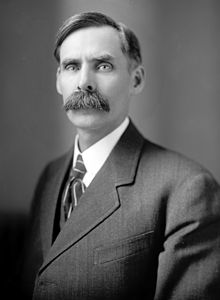

Been watching HBO on Sunday nights lately? Curious about how Steve Buscemi was able to run an empire from the boardwalk in Atlantic City? Now is your chance to enjoy an in person experience with America’s most fascinating and misguided era, Prohibition. Minnesota residents should be especially aware of this lapse in judgment as it was a congressman from district 7 of our state, Andrew Volstead that authored this law. From November 9th to March 16th the Minnesota Historical Society is giving us the chance during our longest season, winter, to warm our spirits with, well, spirits. Starting today the History Center will be featuring American Spirits: The Rise and Fall of Prohibition presented by the National Constitution Center.

Been watching HBO on Sunday nights lately? Curious about how Steve Buscemi was able to run an empire from the boardwalk in Atlantic City? Now is your chance to enjoy an in person experience with America’s most fascinating and misguided era, Prohibition. Minnesota residents should be especially aware of this lapse in judgment as it was a congressman from district 7 of our state, Andrew Volstead that authored this law. From November 9th to March 16th the Minnesota Historical Society is giving us the chance during our longest season, winter, to warm our spirits with, well, spirits. Starting today the History Center will be featuring American Spirits: The Rise and Fall of Prohibition presented by the National Constitution Center. Over the course of the next few months the History Center will be featuring different events highlighting some of the impacts of results of the Prohibition Era. One of these events that I will definitely been attending is the Speakeasy Saturdays reflecting the revival of local brewing and distilling. This event will feature Summit Brewing, Great Waters Brewing, and Dashfire Bitters on Saturdays from December through February. Other events during this exhibit will include a musical performance called A Toast to Prohibition: Songs of Temperance and Temptation, an ongoing series called History Lounge featuring discussions with historians, and Bootleg Valentine: Dining, dancing, and romancing in Prohibition Era Twin Cities.

Over the course of the next few months the History Center will be featuring different events highlighting some of the impacts of results of the Prohibition Era. One of these events that I will definitely been attending is the Speakeasy Saturdays reflecting the revival of local brewing and distilling. This event will feature Summit Brewing, Great Waters Brewing, and Dashfire Bitters on Saturdays from December through February. Other events during this exhibit will include a musical performance called A Toast to Prohibition: Songs of Temperance and Temptation, an ongoing series called History Lounge featuring discussions with historians, and Bootleg Valentine: Dining, dancing, and romancing in Prohibition Era Twin Cities.